This blog is the first in a series describing adversaries and their motivations. This part in the series presents underlying concepts and the value proposition for exploring who is attacking a network and why.

Intelligence Driven Computer Network Defense

The modern Computer Network Defense (CND) staple of intelligence driven operations (PDF) is based on the observation that incidents are not singular events, but rather phased progressions. In this model, defenders benefit from a cohesive view of adversaries operating inside of a network (also referred to as viewing an adversary in the aggregate). This enables defenders to not only detect today’s threats but also leverage a scientific, evidence-based approach to engage tomorrow’s evolving threats. At its roots are the identification, analysis, and tracking of instances an actor interacted with a network and their respective direct and indirect activity as they worked towards one or more objectives.

For networks with strongly architected and implemented security, an abundance of information is available to support preventive strategies and enable more efficient and effective CND. Organizations focused on the development and continuous improvement of their CND people, processes, and technology can glean significant intelligence from this information, which can then be incorporated into a continuous feedback loop for progressively stronger defense.

For any incident, there’s an inherent trade-off between completeness of investigation (i.e., qualification, quantification) and time to closure (i.e., point of containment, lasting remediation). Organizational leadership traditionally focuses on answering the “what”, “when”, “where”, and “how” questions surrounding a security event or incident, which is understandable, considering that this information helps explain risk in quantifiable terms to key stakeholders across the business. However, the sometimes overlooked “who” and “why” questions for an incident are also valuable and – if properly applied – can significantly benefit an organization on both strategic and tactical levels, leaning into proactive (versus reactive) territory.

Maximizing the Benefits of Threat Intelligence

Optimizing integration of the 5 W’s and 1 H into CND operations allows an organization to maximize the benefits of its threat intelligence capabilities. Each of these factors augments and further qualifies the others to various degrees. Specifically, answers to “who” and “why” can be extremely useful to a network defender towards additional context on an attack, whether responding to an alert for a proactive network block or identifying the next generation of malware found through automated dynamic analysis or incident forensics. Specifically, these factors support more informed decision-making to find a sweet spot where defenders have enough information backed by actionable context to make the best decisions possible regarding defensive priorities, controls, processes, and activities.

Integrating “who” and “why” into the equation contributes to:

- Isolating employed Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs)

- Detecting and mitigating attacker tools

- Assessing actor sophistication and funding

- Gauging attacker commitment and persistence

- Tracking actively targeted technology, information, and personnel

The broader implications of these gains include:

- Refined prioritization of resources (e.g., personnel, assets, funding)

- More efficient and effective CND operations (i.e., working smarter, not harder)

- Improvement of overall security posture (i.e., increasing the resource cost for an adversary)

Malicious Actor Motivations

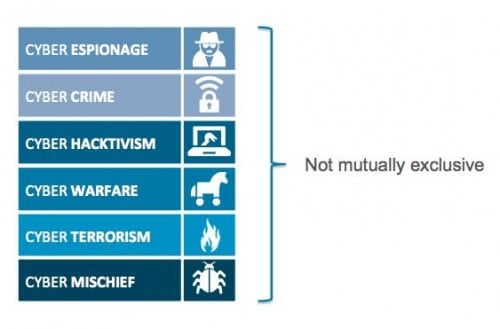

At the end of the day, malicious actors are people too. Underlying motivations drive their activities in support of respective objectives. Unit 42 recognizes six top-level motivations:

- Cyber Espionage: Patient, persistent and creative computer network exploitation for strategic economic, political and military advantage

- Cyber Crime: Extension of traditional criminal activity, focused on personal and financial data theft

- Cyber Hacktivism: Activist cyber attacks seeking to influence opinion and / or reputation for specific organizations, affiliations or causes

- Cyber Warfare: Cyber operations that alone or in complement to kinetic / physical operations destroy or degrade a target country’s capabilities

- Cyber Terrorism: The convergence of cyberspace and terrorism, causing loss of life or severe economic damage

- Cyber Mischief: Arbitrary and / or amateur cyber threat “noise” on the Internet

Figure 1. High-level malicious actor motivations

We prepend “Cyber” to each of these not so much due to a fondness for this oft-overused term, but rather as a reminder that these core motivations existed long before their use with regards to computer networks and systems. In short, “cyber” is just another medium over which malicious actors have chosen to achieve their objectives.

An important take-away is that these top-level motivations are not mutually exclusive. Think of them as “hats” an attacker can wear at any given time. In other words, an attacker might wear one or more “hats” for any single attack. As an extension of this view, they can choose to operate based off of multiple motivations across one or more attack campaigns. Additionally, dynamic factors may influence actor motivation for a given attack, such as integration of information gleaned from progressive operations and identification of targets of opportunity. More advanced and/or creative adversaries may actively engage in misdirection and suggest one motivation, when in reality their objectives are based on another.

Although motivations may shift for a single actor, most actors will often employ the same Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures (TTPs); malware and tools; and/or other resources (e.g., infrastructure providers) across all of their operations. This majority will often not stray far from a core set of capabilities and methods. However, the following trends have added to the complexity of identifying malicious actor motivation and establishing attribution:

- Success experienced by one malicious actor group in attacking the people, processes, and/or technology of an organization emboldens and inspires others to integrate similar or evolved methods

- Adoption and customization of publicly-available malware and tools, shared across many actor motivations and groups

- Closed source sharing of malware, tools, and infrastructure

Levels of Attribution

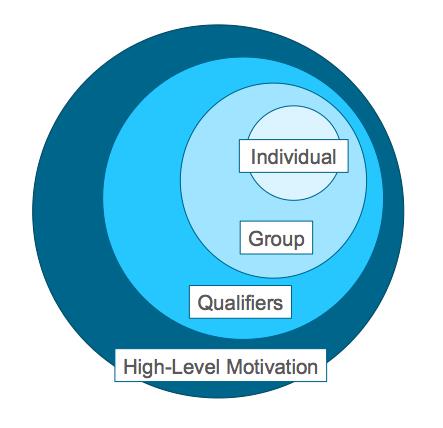

When it comes to the concept of attribution, isolating who is behind a security event or incident, there are potential benefits to keeping track of even the most fundamental characteristics of an attacker. An organization doesn’t need to jump straight in to identifying individuals to benefit from information collected on a malicious actor; in fact, gradually building out attribution capabilities is a more sustainable practice.

Figure 2. Levels of attribution

Attribution can occur at varying granularity and applies to each “hat” an adversary might wear at any given time. The conceptual levels (from least to most granular) behind this idea follow:

- High-Level Motivation: Previously described above and typically the easiest level to establish

- Qualifiers: Include aspects such as preferred targeting (e.g., industry, affiliation, types of information, etc.), activity sponsorship (i.e., scale and funding), and potential correlation / relationship with other threat actor groups or events (e.g., real world or virtual; security event related or otherwise newsworthy such as politics or legislation)

- Group: Includes isolation of TTPs, distinguishing malware and / or tools, attack infrastructure, and degree of cohesion (i.e., formal organization versus self-identifying / collective)

- Individual: The most difficult level to establish, especially for advanced / sophisticated adversaries; may include deeper threat intelligence aspects gleaned or leaked for very specific attack operators (e.g., distinguishing “calling cards”, competitor doxing, law enforcement operations)

Bringing It All Together

When viewed holistically in conjunction with other information security activities (e.g., broader risk assessment), even just recognizing a high-level motivation can assist in tailoring defenses accordingly. Tying this concept back to viewing an adversary in the aggregate, each contact with that adversary is an opportunity to further track and refine attribution. Progressively finer granularity of attribution allows for an increasing degree of focus in defensive operations. This in turn reduces the resources required for reactive incident response and gives defenders enough breathing room to expand on proactive defensive measures.

Coming Up…

The next blog for this series will take a closer look at three top-level malicious actor motivations: Cyber Espionage, Cyber Crime, and Cyber Hacktivism.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.