This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Threat actors constantly hunt for evasion and anti-analysis techniques in order to increase the success rate of their attacks and to lengthen the duration of their access on a compromised system. In some cases, threat groups use techniques they find discussed on the Internet during their operations, such as the Office Test Persistence method that the Sofacy group found within a blog published in 2014. While analyzing a recent attack that occurred on August 10, 2016, we observed an interesting anti-analysis technique used by the Dukes threat group (aka APT29, CozyBear, Office Monkeys) that we had not seen in the past. The use of the anti-analysis technique that we will discuss in this blog confirms that this threat group continually researches new anti-analysis techniques.

Malicious Macro

In an attack that occurred on August 10, 2016, the Dukes group used a malicious OLE file (SHA256: 23a8a6962851b4adb44e3c243a5b55cff70e26cb65642cc30700a3e62ef180ef), specifically an Excel spreadsheet (.xls) that contained a macro that drops and executes a malicious payload. The malicious payload is a dynamic link library (DLL) that the macro saves to the following location:

%APPDATA%\Adobe\qpbqrx.dat

Once the DLL is saved to the system, the macro executes the payload using the following command line:

rundll32.exe %APPDATA%\Adobe\qpbqrx.dat,#2

The "#2" in the command above signifies the exported function within the DLL that the rundll32 application will treat as the entry point of the DLL. In this case, the rundll32 application will call the exported function at ordinal 2 instead of using an exported function name.

Anti-analysis Trick

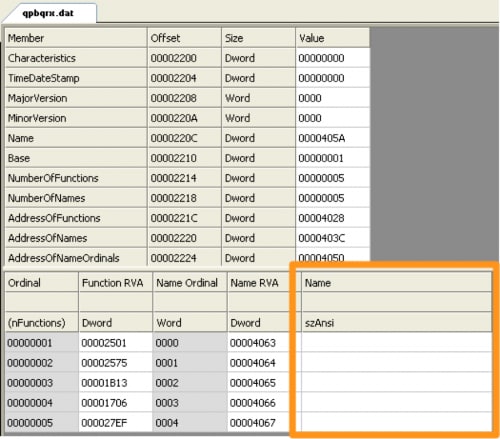

Calling exported functions by ordinal is not a new or unique technique by any means, but this is where the story gets interesting. Using the exported functions by ordinal meant the exported function name was unnecessary, which allowed the developer of this DLL to leave the names for the exported functions blank, as seen in the orange box in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Exported Address Table of Dukes Payload Showing Blank Function Names

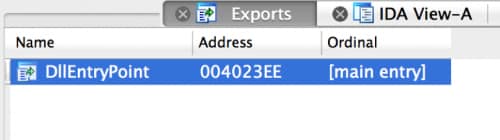

What is the significance of leaving these exported function names blank? The first and the obvious reason is that malware analysts cannot use the function names to correlate related samples. The less obvious reason is that it takes advantage of a bug in the popular IDA disassembler that was recently fixed in the latest version of IDA. Figure 2 shows the DLL opened in a recent (but not the latest) version of IDA, specifically version 6.9.160222. The exports tab shows the only exported function is DllEntryPoint and does not display any of the other functions with blank names.

Figure 2 Duke Payload Opened in IDA version 6.9.160222 Showing Only One Exported Function

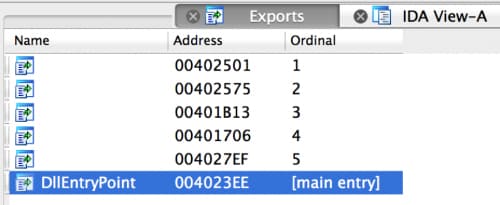

Figure 3 shows the DLL opened in the latest version of IDA, specifically version 6.95.160808 that shows all of the exported functions, their blank names and their respective ordinals.

Figure 3 Dukes Payload Opened in IDA 6.95.160808 that Shows All Exported Functions

With the Quickness

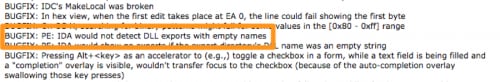

During our analysis, we sought to find the reason behind the discrepancy in displaying export functions between the two versions of IDA. According to the release notes for IDA version 6.95, the IDA disassembler would not detect and would not display a DLL’s exported functions if the names were empty, as seen in the orange box in Figure 4. This blank export name technique is an anti-analysis technique that could increase the difficulty in analysis for those malware analysts that do not have the most updated version of IDA.

Figure 4 IDA Bug Fixes Showing DLL Export Issue

The release notes for this version of IDA were posted on August 8, 2016, which was two days before the attack delivered the payload leveraging the technique. We believe this threat group either found this bug in IDA that caused the bug fix or the group monitors IDA release notes for bug fixes to figure out how to make analysis difficult. While we cannot know for certain, we believe the latter to be the more plausible explanation due to the sequential order of the IDA release notes and the attack date. Also, the latter would suggest that the group is able to quickly find anti-analysis opportunities and deploy the techniques within their toolset.

Conclusion

Threat groups research new techniques to evade detection and increase the difficulty needed to analyze their payloads. Not all research is based on organic efforts within the threat group, as we can see from this incident that the group appears to obtain techniques from open sources on the Internet. In this case, the Dukes threat group knows that malware analysts tasked with reverse engineering their tools typically use the IDA disassembler. It appears this group looks for ways to evade analysis tools, specifically in this case by monitoring release notes from known malware analysis tools to deploy their own countermeasures. Let this be a reminder to those running older versions of IDA to update in order to keep up with the threat groups anti-analysis techniques.

We will continue to provide details as appropriate about this incident and the involvement of the Dukes threat group, including our observations of overlap in targeted organizations and individuals, technique overlap with known Dukes tool HAMMERTOSS — specifically the use of images land steganography to download secondary payloads — and the use of compromised servers to host C2.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.